Short-term contracts, dismantled infrastructure and lagging dayrates have long challenged shallow water drilling on the U.S. side of the Gulf of Mexico – but it’s the natural gas-belching shale plays that may finally turn the tide away from the shelf.

In January 2007, there were 82 jackup rigs drilling in the shallow water of the U.S. Gulf (GOM). By January this year, that figure had dwindled down to 12. At the end of March, 11 jackups remained on the shelf, according to Rigzone Data Services.

McDermott International Inc. began its exit from the U.S. shallows six years ago, said Scott Munro, McDermott’s vice president for the Americas, Europe and Africa.

“There’s not much of the (U.S. GOM) shallow water that hasn’t been explored or attempted. Most of the low-hanging fruit has been taken; most of the big oil opportunities have been taken,” he said. “What was left really was gas opportunities … But then what happens? Mr. Shale shows up and the onshore shale plays just spit out gas as a by-product of oil production and so no one is spending a lot of money to develop offshore gas. It’s only if you can get out a nice oil find that people are really spending.”

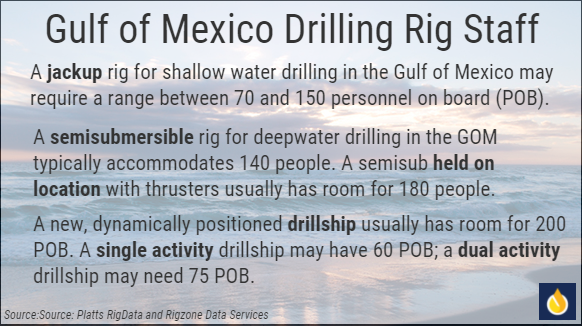

A jackup requires up to 150 personnel on board (POB), according to Rigzone Data Services and Platts RigData. At a drop from 82 jackups to 11, that’s up to 10,659 jobs that won’t be coming back.

“I’m no economist, I’m no soothsayer, but I would say the chances of shallow water coming back in the USA coming back in any meaningful way is slim,” Munro said.

Shelf Life

Houston Energy Inc., and its partners waded into the Gulf of Mexico in the early 1990s, said Ronald Neal, co-founder and co-owner of the private exploration and production (E&P) company. The plan was to follow the majors to drill in shallow water as a consortium of four member companies: with Houston Energy, LLOG Exploration Co. is the operating partner; Ridgewood Energy Corp. raises capital and invests in the partnership; and Red Willow Production Co., a sub-unit of the Southern Ute Indian tribe of southwest Colorado. Houston Energy’s role is primarily to generate prospects. It’s the only such partnership in the Gulf of Mexico.

The majors were the first to drill in the Gulf of Mexico, and they established fields and produced a lot of oil and gas, Neal said. But as the 2000s ticked by, those large, publicly traded players were abandoning the shelf for the promise of deepwater.

“The size of the prize – how big the fields that were typically being found in shallow water – were much smaller and did not have any impact on (majors) needs. When they began to decrease their activity, the independents, the smaller public companies or the private companies began to move into the shelf,” Neal said. “We thought that same would occur in the deepwater. Potentially the majors took the initial risk, made the initial discoveries, proved the deepwater was viable as an oil province and put in a lot of the initial infrastructure. We felt there could be a niche to repeat our model on the shelf.”

Deepwater has transitioned through the downturn, Neal said, but the economics didn’t get as bad there as they did on the shelf.

“I don’t know if the shelf will ever recover,” he said. “The ‘size of the prize’ – it’s generally smaller and it’s generally gas, so that makes the economics much more difficult. Also, as the shelf has been producing out, the fields, the platforms have to be removed and the pipelines have to be abandoned. The infrastructure that you had in place to be able to tie into with your production is being removed.”

The Biggest Jackup Market in the World

There was a time when the Gulf of Mexico ruled the jackup market. With almost 200 jackups, the shelf was the biggest jackup market by far, said Terry Childs, director of Rigzone Data Services.

Rowan, Ensco and Enterprise, which bought the now-defunct Hercules Offshore assets, run the majority of the jackups in the GOM. They number less than a dozen, and Childs said it’s unlikely there will ever be more such rigs on the shelf.

“All the regions of the world that have mature shelf basins – the North Sea, Southeast Asia and West Africa – their jackup activity isn’t probably what it once was either, but I don’t think there’s any region that has declined like this one,” he said.

Today, the Middle East’s jackup market is the largest shelf drilling area in the world, Childs said. With a breakeven at $27 per barrel of oil, producers there aren’t motivated much by price fluctuations. Since September 2014, the Middle East market has only lost 10 rigs, dropping from 116 jackups to 110 rigs. Conversely, the GOM count has declined from 37 jackups to 11 rigs at the end of March.

It’s the short-term contracts and lower dayrates that have mostly driven producers away from the Gulf’s shallow water, he said. Contracts in the GOM can be signed on a week or two’s worth of work; rigs in other shallow water plays can be tied up for years.

“This market is done, in terms of ever having a lot more jackups. It’s just not going to happen,” Childs said. “Here, deepwater is clearly where the focus is in the future. The only reason there’s as many jackups still existing in supply as there is, is because they just haven’t scrapped them yet.”

source: http://www.rigzone.com/news/oil_gas/a/150076/All_Washed_Up_Shale_Oil_and_Gas_Drowns_Out_US_Gulf_of_Mexico_Shallows/?pgNum=1