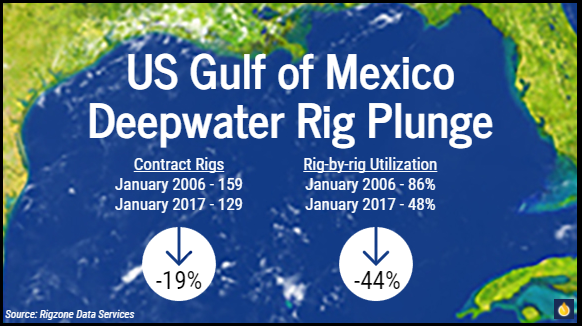

Efficiency and historic investment in legacy U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GOM) deepwater fields are flooding inventories this year, but along with the rig count, deepwater investment there continues to plunge.

“The CAPEX number for 2017 is going to be pretty flat,” said Imran Khan, senior research manager for GOM deepwater at Wood MacKenzie (WoodMac). “There was a big drop in previous years, so we’re already looking at a pretty low number for 2016. We’re going from about $12.2 billion to about $10 billion for 2017.”

But less capital expenditures (CAPEX) isn’t reflected by current deepwater production. In January, U.S. production in the GOM grew for the fourth consecutive month, reaching 1.7 million barrels per day (MMbpd) and obliterating the annual record high set in 2016 of 1.6 MMbpd, which had knocked 2009 out of the top spot, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Prior to the downturn, significant capital was deployed in the Gulf, which has allowed large fields, such as BP plc’s Mad Dog and Thunderhorse, to crank out hydrocarbons without additional significant capital. As the rigs that are in action ramp up, their forward breakevens are between $25 and $35 per barrel, Khan said.

“You do have to keep in mind that prices have come down, and operators are getting better at drilling wells so it’s costing them less to do the same,” Khan said.

In the not-too-distant future, though, investment in the Gulf must rebound, said Dan Pickering, president and head of TPH Asset Management at Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co., during a May 2 presentation at the Offshore Technology Conference in Houston.

Global crude oil demand has increased by at least 2 percent for most year-to-year averages. But even the most prolific majors in the GOM have drilled dry holes, Pickering said. During the last three years, TPH has modeled production on a 50 “wells to watch.” That research has found that 69 percent of the new wells are dry; 16 percent are unclear; and 16 percent are commercially viable. That makes replacing reserves to meet future demand a serious challenge.

TPH’s findings are sobering, Pickering said. On a five-year average replacement basis, none of the major oil companies have been able to replace their deepwater reserves at 100 percent. In fact, the average replacement rate of the biggest players – ExxonMobil Corp., TOTAL SA, Chevron Corp., BP and Royal Dutch Shell plc – is 42 percent.

Between 2010 and 2014 – when global oil prices were generally close to $100 per barrel – the biggest deepwater producers lost 2 MMbpd in oil equivalent, he said.

“Even when prices were great, these companies were having trouble growing on the oil side,” Pickering said.

And so, deepwater is an answer to how to boost volume, but it’s one that’s challenged by $50 oil. The contraction in cash flow – along with the economics of drilling in the vast, deepest parts of the ocean – are tricky, he said.

“Volatility of price makes it tough to commit to projects that take six, eight, 10 years to go from concept to first production to cash flow,” he said.

Private equity is one way to address the cash flow issue, but price volatility historically has unnerved that market. A new approach to attracting private equity is key to finding the intersection between that cash, Pickering said.

Deepwater Versus Tight Oil

There’s certainly money to be made in the Gulf of Mexico, said Dave Pursell, managing director and head of macro research at Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co., but it’s not for everybody.

“Would you rather go into the Gulf of Mexico, or would you rather pay $40,000 an acre for West Texas assets? It probably depends on your skillset,” he said. “The Gulf isn’t dead, but it’s a certainly off-the-radar screen opportunity.”

Moving on a $15 billion deepwater project before a single dollar shows up on the balance sheet can be a tough sale.

“How can (a producer) sanction that project if a bunch of guys are drilling everybody’s collective brains out in West Texas?” Pursell said. “Don’t we have to wait – not only for a price signal to tell us to sanction, but don’t we have to wait and see how much production growth is materializing in West Texas and how quickly?”

But could the immense potential of deepwater reserves swipe investment dollars away from relatively cheap-to-develop, prolific shale plays on dry land?

“Clearly a lot of the operators don’t think so because they’re not investing in it,” Khan at WoodMac said. “But at the end of the day, I think the majors do realize they need these big projects to move their needles. They need reserve growth. They need production growth. They’re not going to get that out of tight oil.”

Oil prices have increased in recent months, stabilizing close to $50 per barrel. But to proceed with major investment, operators need to see the price point remain steady for several years, he said.

“Just because oil spikes to $55 doesn’t mean they’re going to make the decision to move forward on a $10 billion project,” he said. “They have to have conviction that $55 oil is there for an extended period of time for them to move forward.”

source: http://www.rigzone.com/news/oil_gas/a/150036/New_Investment_Crucial_to_Keep_Deepwater_US_GOM_Production_Afloat/?pgNum=1